A group of scientists concerned about the thousands of species facing extinction believes that their salvation lies not here on Earth, but more than 230,000 miles above it.

If calamity strikes our planet, a team at the Smithsonian argues that the only way to protect the DNA of those at-risk creatures is to get it as far away from Earth as possible.

Their radical plan? Load those samples up onto a cosmic Noah’s Ark and ship them off to the moon.

In the proposal, published in July in the journal BioScience, an international team of experts provides an outline for how a lunar biorepository could feasibly be created.

The idea, which has been suggested before, involves storing the DNA of threatened animals in a vault on the lunar surface – Earth’s only natural satellite – where conditions are cold enough to preserve the samples. The method would also have the added benefit of stationing the biorepository of preserved cells well beyond the reach of any number of disasters that threaten our planet, from climate change to geopolitical strife.

A similar concept was outlined in 2021 by a group of researchers at the University of Arizona, who presented a paper for a “modern global insurance policy” at that year’s IEEE Aerospace Conference.

Were the plan to ever be accepted by the global community, it would still be decades before any kind of spacecraft would be making the lunar voyage with the genetic makeup of any number of species on board. But the experts insist urgent – and drastic – action is required to protect a multitude of critically endangered species.

Here’s a look inside the proposed lunar Noah’s Ark – the plan to essentially build a large freezer to cryogenically preserve animal DNA on the moon.

Why the moon?

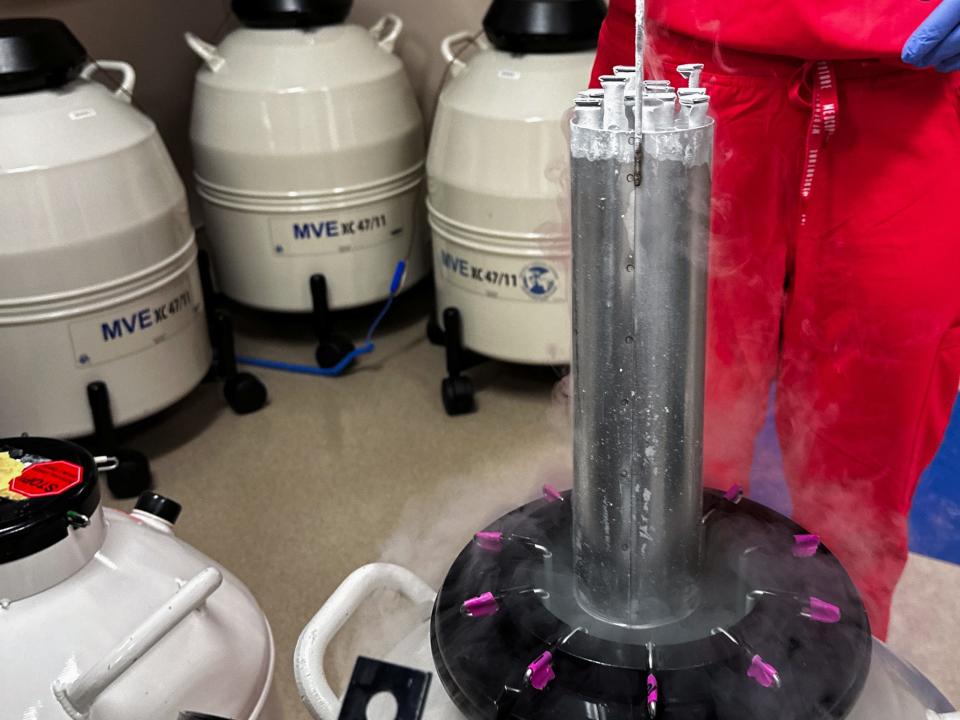

Here on Earth, cryogenic preservation requires electricity and liquid nitrogen to accomplish.

But on the moon, the celestial body’s shadowed craters create conditions frigid enough to keep DNA samples frozen year-round without the need for human intervention, the team wrote in their proposal. The deep craters near the polar regions are never exposed to sunlight, making those areas of the moon one of few places to reach the ultra-low temperature of -410 degrees Fahrenheit – cold enough to preserve cryogenically frozen animal skin and tissue for future cloning.

Of course, a global seed vault already exists in Svalbard, Norway to safeguard biological samples. The vast repository located hundreds of feet underground on a remote Norwegian island in the Arctic Circle contains more than 1 million frozen seed varieties to ensure the world’s crop biodiversity is protected in the case of global disaster.

But even the Svalbard seed vault has proven vulnerable to Earth-borne dangers when thawing permafrost threatened to flood and destroy the stockpile in 2017.

By virtue of being far, far away from Earth, the moon is not susceptible to planetary disasters of both the natural and human-made variety, the researchers argued. Storing the preserved cells and the crucial DNA within them on the lunar surface would ensure the biorepository would remain relatively protected until the need arises to use the samples to enhance genetic diversity or clone new animals altogether.

A desire to protect critically endangered species

The experts crafted the proposal out of alarm for the growing number of threats making it difficult to protect natural habitats and the animals that call them home.

More than 45,300 species worldwide are threatened with extinction, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. The extinction rate is so severe that several advocacy organizations have referred to it as a crisis – and one almost entirely of our own making, fueled by habitat destruction, pollution, overharvesting and population growth.

“Initially, a lunar biorepository would target the most at-risk species on Earth today,” the proposal’s lead author, Mary Hagedorn, a research scientist at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute, said in a statement . “But our ultimate goal would be to cryopreserve most species on Earth.”

How creating a lunar Noah’s ark would work

Cryopreservation may conjure with it images and associations straight out of a science fiction movie, but the process is one that has entered the realm of reality.

Already, cryopreservation plays an important role for in vitro fertilization (IVF,) which involves freezing and storing fertilized eggs for later use.

For the proposed lunar biorepository, the team suggests cryopreservation – or deep freezing the animals’ cellular material to induce suspended animation – would be pivotal to ensure the samples’ longevity. At low enough temperatures, all biological activity effectively comes to a halt.

The samples could then be stored underground or inside a human-made structure to block out the damaging radiation in space.

If it sounds outlandish, it’s a process the Smithsonian researchers have already been testing. The team claims to have already preserved the living cells from the starry goby fish, a creature that is not yet endangered but whose existence helps sustain the coral reefs.

For the test, the team preserved the species’ skin cells, called fibroblasts. As opposed to other types of commonly cryopreserved cells like sperm, eggs and embryos, fibroblasts are much more easily collected and stored, the team wrote.

Growing interest in lunar exploration

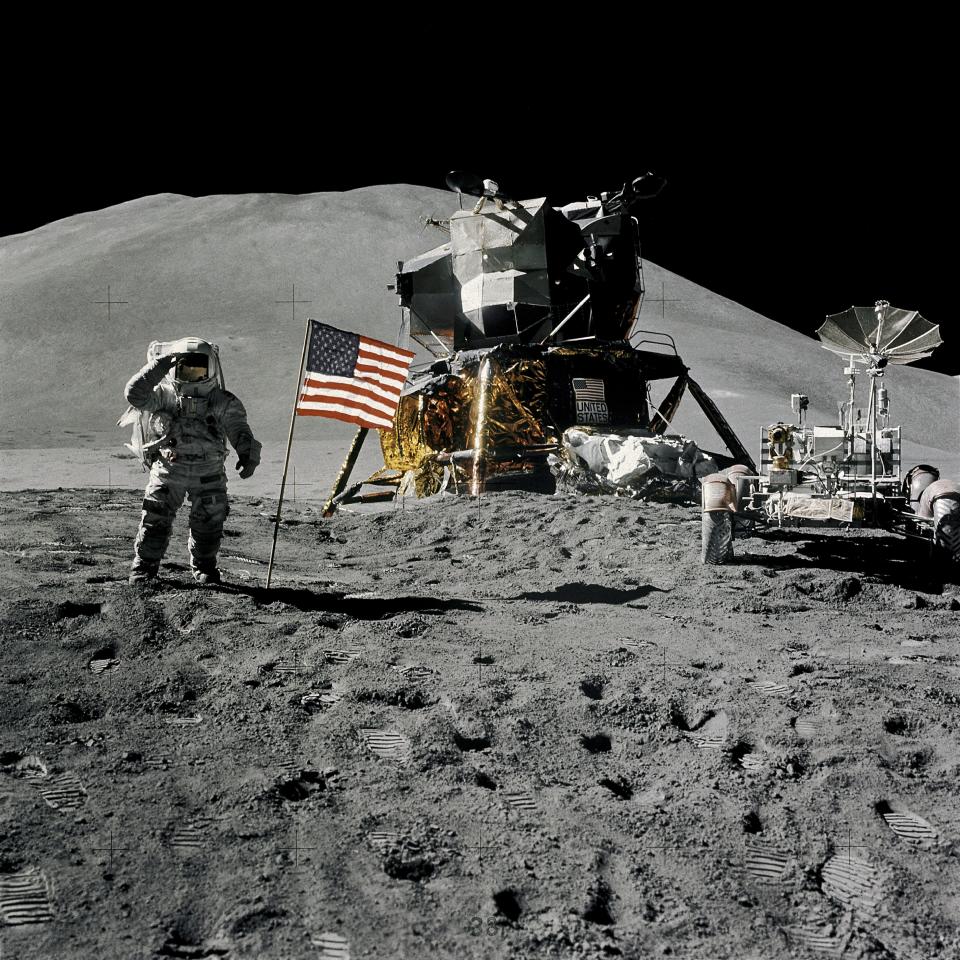

The proposal for the lunar biorepository comes as NASA and other space agencies around the world are eyeing further exploration of the moon in coming years.

For NASA, its Artemis program aims to land astronauts on the lunar surface as early as 2026 for the first time since the agency’s Apollo program came to an end in the 1970s.

And once Americans make it back to the moon, they don’t intend to leave it anytime soon. In the years ahead, the U.S. space agency hopes to establish a lunar settlement on the south polar, using the region’s abundant water ice for drinking, breathing and as a source of hydrogen and oxygen for rocket fuel to make further deep space exploration possible.

With so many lunar journeys on the docket, Hagedorn and her team don’t see why one of those upcoming launches couldn’t also deliver some small parcels containing cryopreserved samples of endangered species.

The team is already at work conducting radiation exposure tests to help design packaging to safely deliver the samples to the moon and is actively seeking partners for further research and funding.

“This is meant to help offset natural disasters and, potentially, to augment space travel,” Hagedorn said.

Lunar biorepository may not happen in our lifetime

But a lunar Noah’s Ark is still a long way away from becoming reality.

The “decades-long program,” as the team referred to it, would be a massive and costly undertaking, requiring international cooperation. It’s ambitious, to be sure, but not unrealistic, Hagedorn argues.

For now, the researchers are simply hoping to get their wild plan out there and perhaps spark some conversation – and even some controversy.

“We hope that by sharing our vision, our group can find additional partners to expand the conversation, discuss threats and opportunities and conduct the necessary research and testing to make this biorepository a reality,” Hagedorn said in her statement. “Life is precious and, as far as we know, rare in the universe. This biorepository provides another, parallel approach to conserving Earth’s precious biodiversity.”

Eric Lagatta covers breaking and trending news for USA TODAY. Reach him at [email protected]

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Lunar Noah’s Ark? Inside a plan to store DNA of animals on the moon