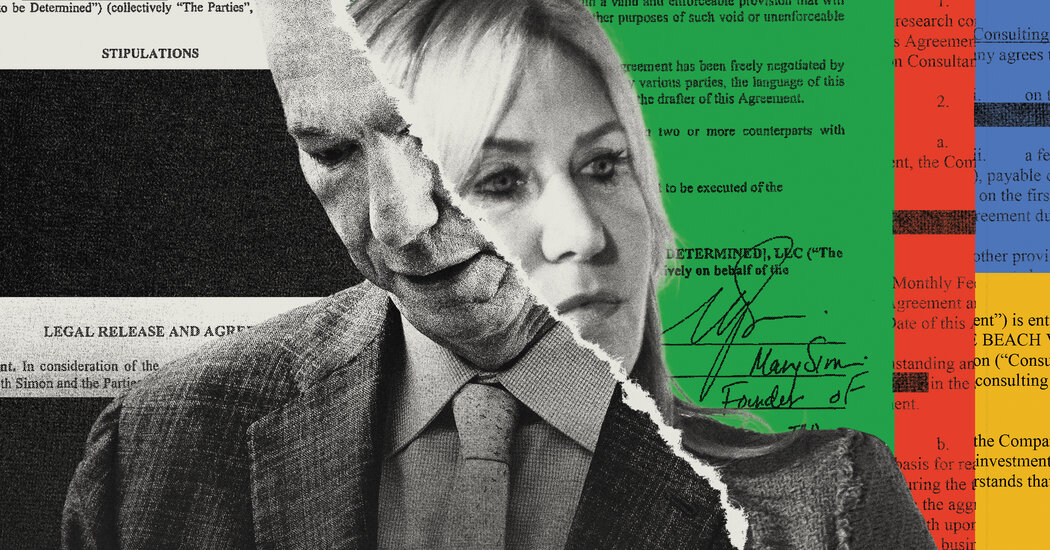

The End of the Affair? Not for Eric Schmidt.

When Eric Schmidt was the chief executive of Google in the mid-2000s, he dated Marcy Simon, a New York-based public relations executive. Both were married to other people at the time.

Mr. Schmidt and Ms. Simon were seen together on the French Riviera, at tech conferences and on Fire Island, where she owned a beach house. When a large yellow diamond ring was spotted on Ms. Simon’s finger, some speculated in the media that Mr. Schmidt might divorce his wife and marry Ms. Simon.

But Mr. Schmidt moved on to other girlfriends. Although he and Ms. Simon, who divorced her husband, later rekindled their relationship in the late 2000s and early 2010s, they decided to go their separate ways in 2014, people with knowledge of their relationship said.

For billionaires, and the people who love them, breaking up can be a little like unraveling a corporate merger gone wrong. Ending Mr. Schmidt’s affair has taken a decade — so far. There have been contracts, amended contracts, arbitrations, lawsuits and the platoon of advisers that inevitably go along with all that.

Mr. Schmidt, now 69 years old, approved a confidential settlement in 2014 with Ms. Simon that paid her an undisclosed amount of money, and appointed an adviser, Derek Rundell, to set it up. Under the arrangement, Ms. Simon would bring Mr. Schmidt investment ideas that Mr. Rundell would evaluate on his behalf.

But the deal imploded when Ms. Simon and Mr. Rundell fought bitterly, leading to years of wrangling that culminated in accusations of fraud against Ms. Simon last year over an investment in the luggage maker Away. Ms. Simon has denied committing fraud.

During his years leading Google, Mr. Schmidt was famously known as the adult supervision, a brainy, button-down sage who mentored the internet firm’s young founders, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, and propelled the company to great heights. Since leaving the board of Google’s parent company in 2019, he has cultivated that image further, parlaying his net worth of about $35 billion into an influential role advising the U.S. government on defense and artificial intelligence policy and making his mark with splashy initiatives in the world of philanthropy.

Yet over the past decade, his management of personal matters has been fraught, at times lacking the kind of discipline he brought to running Google. In March, Ms. Simon filed an arbitration case against Mr. Schmidt in California, seeking to free herself from the confidentiality clauses of their 2014 settlement. More of his secrets threaten to spill out.

The New York Times pieced together Mr. Schmidt’s tangled history with Ms. Simon and Mr. Rundell from records of six separate litigation and arbitration cases, all of which are public. Mr. Schmidt’s name is redacted or withheld in four of the cases, but The Times confirmed his identity through people with knowledge of some of the events and by triangulating information from court filings.

Ms. Simon, 61, who left the public relations firm Burson-Marsteller and founded her own public relations company in 2019, was one of a series of women with whom Mr. Schmidt had extramarital affairs over the past 20 years. Throughout, he has remained married to Wendy Schmidt, his wife of 44 years, though they lead largely separate lives.

In a 2012 interview with The Times, Ms. Schmidt shrugged off media reports of her husband’s relationships. “You know, people will write things,” she said. “You just have to ignore them.”

Mr. Schmidt and Ms. Simon started appearing publicly together in the mid-2000s. Neither made much of an attempt to keep the relationship secret; Ms. Simon openly talked about it with some journalists.

After a hiatus of a few years during which Mr. Schmidt dated a former CNBC reporter, Kate Bohner, he and Ms. Simon got back together in 2009 and saw each other on and off for several more years. In the summer of 2014, they parted ways.

Mr. Schmidt had paid certain expenses for Ms. Simon for years, which were memorialized in several legal agreements. He proposed a new financial arrangement to provide for Ms. Simon and her family, people with knowledge of the conversations said.

Mr. Schmidt put Mr. Rundell in charge of crafting the deal.

Mr. Rundell had entered Mr. Schmidt’s orbit through Gary Coursey, a financial adviser known by the nickname Court who helped Mr. Schmidt make venture capital investments. Mr. Rundell and Mr. Coursey had met at the University of Colorado Boulder in the early 1990s, later sold an email company to WebMD and briefly advised the pop star Michael Jackson in the early 2000s.

After Mr. Coursey introduced them, Mr. Rundell became something of a fixer for Mr. Schmidt. Mr. Rundell was “a person who could solve special and hard problems,” Mr. Schmidt testified in one arbitration proceeding.

The Information earlier reported on Mr. Rundell’s work for Mr. Schmidt. Mr. Rundell, 53, did not reply to requests for comment.

At Mr. Schmidt’s request, Mr. Rundell put together the confidential settlement with Ms. Simon, which firmly nudged the relationship from romantic to transactional. Under the terms of the agreement, dated Sept. 19, 2014, Ms. Simon agreed to become a paid consultant to a Nevada limited liability company called Maple Beach Ventures.

Maple Beach Ventures was essentially a small venture capital fund managed by Mr. Rundell and funded by Mr. Schmidt. Ms. Simon would receive payments for bringing start-up investment ideas to Mr. Rundell. If Mr. Rundell liked them, Mr. Schmidt would invest in the start-ups through Maple Beach Ventures. The agreement included confidentiality, so Ms. Simon could not disclose Mr. Schmidt’s involvement in the investments.

It’s unclear how much Mr. Schmidt paid Ms. Simon. A copy of the settlement filed in court as part of an arbitration shows that she was entitled to a one-time fee and to annual and monthly payments, but the numbers are redacted. Ms. Simon was also entitled to 20 percent of the profit Mr. Schmidt made from any investment she brought.

Around the time he structured the settlement with Ms. Simon, Mr. Rundell also acted as the go-between for the purchase of a horse farm in New York’s Hudson Valley for another of Mr. Schmidt’s girlfriends, Lisa Shields. For these and other services, Mr. Schmidt paid Mr. Rundell a fee of $47,500 a month until June 30, 2016, according to a copy of their agreement.

The settlement with Ms. Simon didn’t bring peace for long.

Within months, Ms. Simon and Mr. Rundell began butting heads. Ms. Simon complained that Mr. Rundell didn’t act on most of the investment ideas she brought, while Mr. Rundell faulted Ms. Simon for not conducting proper due diligence on the investments she proposed.

In March 2015, Ms. Simon complained to Mr. Schmidt that Mr. Rundell had responded to only nine of the 43 investment opportunities she had presented to him and that Maple Beach Ventures had invested in only six of them. Mr. Schmidt responded that most “VCs see 100 or more deals for every one deal they invest in.”

He suggested a compromise: Ms. Simon could have a sum she invested at her own discretion each quarter, provided she followed a strict due diligence process. (The figure was redacted.)

Following up on Mr. Schmidt’s suggestion, Mr. Rundell sent Ms. Simon a proposal with an updated investment budget and new due diligence procedures. But Ms. Simon turned it down because she found the procedures too onerous and resented that the investments would still have to go through Mr. Rundell, according to arbitration filings.

As Ms. Simon and Mr. Rundell haggled, she flew to Europe to attend a networking event for entrepreneurs in the French Alps. There she met Jen Rubio, who had just co-founded a luggage start-up called Away. Between runs on the slopes of the famed Méribel ski resort, Ms. Rubio mentioned that Away was raising money from family and friends in what is known as a “seed round” and invited Ms. Simon to participate.

A few weeks later, Ms. Simon emailed Ms. Rubio to say she would invest $25,000 through Maple Beach Ventures. Ms. Simon could not disclose Mr. Schmidt’s involvement under their 2014 agreement.

“I am really excited to be a part of Away and also to help watch you grow and build the company and I am here for you,” Ms. Simon emailed Ms. Rubio in April 2015.

Ms. Simon arranged a call between Ms. Rubio and Mr. Rundell to finalize the investment, but didn’t explain who Mr. Rundell was, a person with knowledge of the matter said. Ms. Rubio assumed — incorrectly — that Maple Beach Ventures was Ms. Simon’s company and that Mr. Rundell was an employee who worked for her, this person said.

Ms. Simon’s and Mr. Rundell’s relationship continued deteriorating. Around the same time, Ms. Simon had asked Mr. Schmidt for a loan to buy a house. Mr. Schmidt agreed to lend her the money against the proceeds of an investment he had made in Uber several years earlier. The investment had come from an introduction Ms. Simon had made.

Under a deal that predated their 2014 settlement, Mr. Schmidt had agreed to pay her 10 percent of whatever profit he earned from Uber. But the ride-hailing company was still private, so calculating the value of Ms. Simon’s stake to determine the loan size was difficult. Months of negotiations between Mr. Rundell and a lawyer representing Ms. Simon ensued. At one point, Ms. Simon objected to a $125,000 fee Mr. Rundell wanted to deduct from the loan amount.

In March 2016, the loan negotiations broke down, and Ms. Simon sent Mr. Schmidt an angry email threatening to go public about their confidential deal. Mr. Rundell’s behavior was “not acceptable” and she had “an awesome case here,” she wrote. “This is going mainstream and I am lawyering UP.”

A few hours later, she followed up: “Let me know if you want to take this public.”

Later that year, the two sides resolved their differences. Under an amendment to the 2014 settlement, Mr. Schmidt agreed to make monthly payments of $5,000 and quarterly “catch-up” payments of $15,000 to Ms. Simon, on top of other payments laid out in the original agreement. He also agreed to cover unspecified tuition payments and to reimburse Ms. Simon for the $21,000 she had spent on legal fees.

But within months, Ms. Simon and Mr. Rundell resumed bickering. Ms. Simon again complained that Mr. Rundell was ignoring most of the investment ideas she brought to him. Mr. Rundell responded that Ms. Simon wasn’t giving him the documentation she was required to provide for each investment.

Lawyers were summoned again, but this time no compromise was found.

In June 2018, a lawyer for Maple Beach Ventures informed Ms. Simon that her consulting agreement was being terminated. She responded in April 2019 by starting a confidential arbitration proceeding against the company for breach of contract.

While Ms. Simon’s dispute with Mr. Rundell and Mr. Schmidt escalated, Ms. Rubio’s start-up was thriving. Thanks partly to savvy online marketing, Away’s stylish luggage was becoming ubiquitous at U.S. airports. By early 2019, the New York-based company had sold more than one million suitcases.

That May, just weeks after Ms. Simon took Mr. Schmidt and Mr. Rundell to arbitration, a group of institutional investors led by Wellington Management offered to buy the shares of Away’s early investors at a premium to their original price, in what is known as a tender offer. Away was now valued at a stunning $1.4 billion, up from $7.2 million four years earlier. The 266,638 shares that Maple Beach Ventures had purchased for $25,000 in 2015 were worth $2.83 million.

Away transmitted the tender offer to Ms. Simon. Ms. Rubio remained under the impression that Maple Beach Ventures was Ms. Simon’s company and that the $25,000 seed investment had been made with her money, a person familiar with the matter said.

What happened next is under dispute. In a lawsuit that Away filed late last year against Ms. Simon, the company claimed that she took and profited from shares that weren’t hers. Ms. Simon has countered that the shares were, in fact, hers.

Underlying the disagreement was Ms. Simon’s 2014 deal with Mr. Schmidt. Under its terms, she was entitled to 20 percent of the profit that Maple Beach Ventures reaped from any investment she originated, which would have come to about $561,000 before taxes for Away — but only if she were still employed as a consultant to the company when the investment was sold. Her 2018 termination meant she would get nothing.

That did not sit well with Ms. Simon, so she came up with a subterfuge, according to Away’s lawsuit. Rather than forwarding the tender offer transmittal letter to Mr. Rundell, Ms. Simon created a new Maple Beach Ventures LLC on May 10, 2019. Unlike the original Maple Beach Ventures, which Mr. Rundell had registered in Nevada, Ms. Simon incorporated this one in Delaware and designated herself as its sole principal, Away claimed.

Three weeks later, Ms. Simon signed the tender offer paperwork, presenting the new Maple Beach Ventures as the owner of the shares, according to Away’s lawsuit.

Away said it didn’t spot the alleged sleight of hand when it received Ms. Simon’s paperwork. It canceled the original Maple Beach Ventures’ shares in its company records, reissued them to the investor group conducting the tender offer and wired $2.83 million to a Citibank account that Ms. Simon had created in the name of the new, Delaware-registered Maple Beach Ventures.

Mr. Rundell and Mr. Schmidt, who were never notified about Away’s tender offer, had no idea what transpired, people with knowledge of the matter said.

Ms. Simon has countered in court filings that it was always understood that the Away shares were hers, even though they were held under Maple Beach Ventures’ name. In the court filings, she has said she was being prevented from giving the full story by the confidentiality clauses in the 2014 settlement with Mr. Schmidt.

In late 2019, a few months after Ms. Simon sold the Away shares, Mr. Schmidt’s relationship with Mr. Rundell began falling apart. Mr. Coursey, who had introduced Mr. Rundell to Mr. Schmidt, was now feuding with Mr. Rundell, who owed him money. Mr. Rundell asked Mr. Schmidt to cover his debt, people familiar with the men said.

When Mr. Schmidt refused, Mr. Rundell claimed ownership of the Hudson Valley horse farm Mr. Schmidt had bought for Ms. Shields, according to people familiar with the matter and arbitration filings. (Mr. Rundell had leverage because the farm had been purchased under his name, the people said.) In May 2020, Mr. Schmidt took Mr. Rundell to arbitration over the farm.

To get Mr. Schmidt to back off, Mr. Rundell filed a counterclaim in which he said Ms. Simon and Ms. Shields had threatened to air salacious allegations about Mr. Schmidt’s private life. Among the allegations: that Mr. Schmidt used illicit drugs; that he passed on sexually transmitted diseases to multiple partners; that he participated in orgies and in a sex tape; and that he had sex with prostitutes, according to an arbitration filing made public in court.

Ms. Shields denied making the allegations or having any knowledge of them during the arbitration.

Referring to the allegations, Matthew Hiltzik, a spokesman for Mr. Schmidt, said, “Mr. Schmidt refuses to be intimidated by those who threaten to coerce or extort him.”

While Mr. Schmidt and Mr. Rundell battled, Ms. Simon won her breach of contract arbitration against the original Maple Beach Ventures in January 2021. The arbitrator ordered the company to pay her $461,113, plus interest on a portion of it, and reaffirmed her 10 percent stake in any Uber profit.

The rancor between Mr. Schmidt and Mr. Rundell continued escalating. After prevailing in the dispute over the farm, Mr. Schmidt initiated a second arbitration against Mr. Rundell in late 2021 over Maple Beach Ventures and several other companies Mr. Schmidt had funded.

Mr. Hiltzik said Mr. Schmidt responded to Mr. Rundell’s “tactics by prosecuting and prevailing in two separate arbitrations and recovered millions of dollars.”

During the second proceeding, Mr. Schmidt learned what happened to the Away investment. When one of his employees tried to find out the investment’s status, Away said that Maple Beach Ventures was no longer an investor because Ms. Simon had tendered its shares in the 2019 offer.

Mr. Schmidt was furious. His lawyers threatened to sue Away if his shares weren’t reinstated.

In its lawsuit, Away said it was then that it realized that Maple Beach Ventures wasn’t Ms. Simon’s company. In early 2023, Away settled the matter with Mr. Schmidt by paying him $3.5 million, which included interest.

In November, Away sued Ms. Simon for carrying out what it described as a “fraudulent and deceptive scheme.”

In a statement, an Away spokeswoman said it “has been unfairly drawn into this matter, which does not directly concern us. This has led our company to incur significant expenses, which we are now seeking to recover.”

The case is pending in New York State Supreme Court. Ms. Simon has separately begun an arbitration proceeding against Mr. Schmidt to unshackle herself from the confidentiality clauses of their 2014 deal to better defend herself.

The post The End of the Affair? Not for Eric Schmidt. appeared first on New York Times.